SUNCAT Center

One of the research foci of the Chemical Science Division is the study of Chemical Catalysis at the SUNCAT Center for Interface Science and Catalysis, a partnership between SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the Stanford School of Engineering. Catalysts are materials that can affect chemical reactions without themselves being changed. At SUNCAT, researchers are working on improving catalysts, which are widely used in industry to promote reactions for making fuels, fertilizers and other products. The more sensitive and efficient the catalyst, the less energy it uses and the less waste it leaves behind. Scientists want to reach such a deep understanding of how catalysts work that they can deliberately design them for particular jobs from scratch, and use them to generate and store energy in novel ways.

Some specific areas of our research interest include:

- Understanding of surface chemical processes

- Theoretical and experimental methods in surface reactivity

- Developing databases of surface chemical properties

- Developing science-based catalyst design principles

- Energy Conversion processes

Combining expertise in theory, modeling and simulation, with access to powerful tools for materials characterization such as SLAC's X-ray facilities Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) and Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), researchers at SUNCAT are at the forefront of energy research. Computational research at SUNCAT is performed using a computer cluster which is physically located at SLAC, and additional computing resources that we have access to.

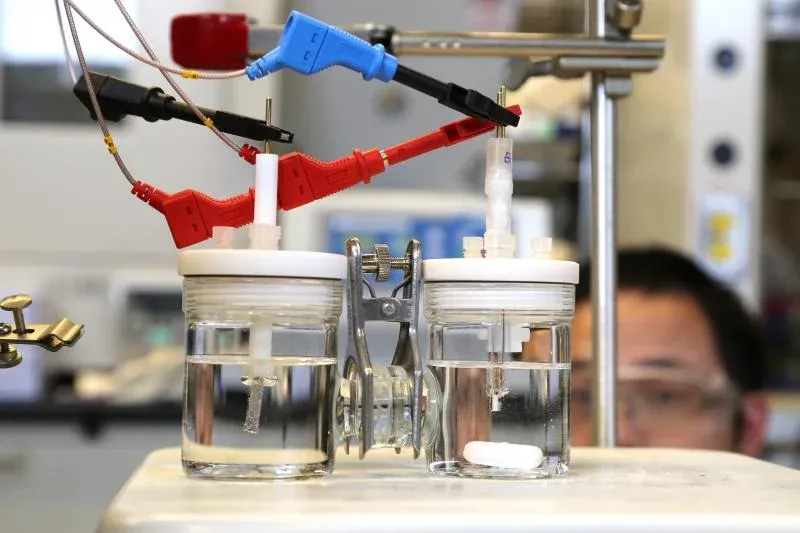

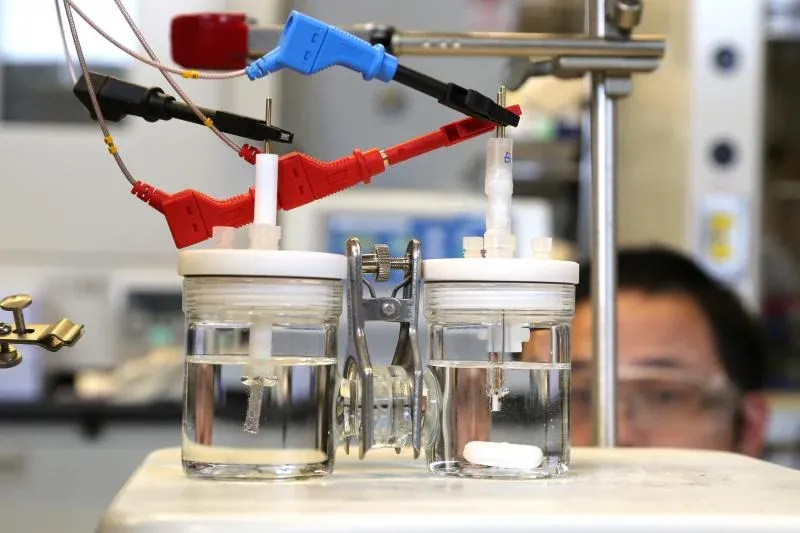

H2O-electrolysing-device2.jpg

One way to store intermittent sun and wind energy is to use it to split water into oxygen and hydrogen as fuel. Now scientists at SLAC and the University of Toronto have invented a new type of catalyst that makes this process three times more efficient. In this water-splitting device on the Toronto campus, hydrogen is bubbling up from the left electrode and oxygen is bubbling up from the right one. (Marit Mitchell/University of Toronto)